The Struggle for Civil Rights, Player’s Handbook (Canada and USA Addresses)

Opening Narrative: Dorchester 1963

There are rocks on the roadside. Though you try to avoid them, one foot or the other keeps turning on a rock or a dusty bottle. The sun’s almost down and you’re lost in the outskirts of Savannah Georgia. As the cars pass by you try not to look, but somewhere in your heart, you know what’s likely to happen next. Someone is going to stop, or call out. Some group of young white men out for a wild time will discover you, a black man walking alone on the roadside, and their fun will begin.

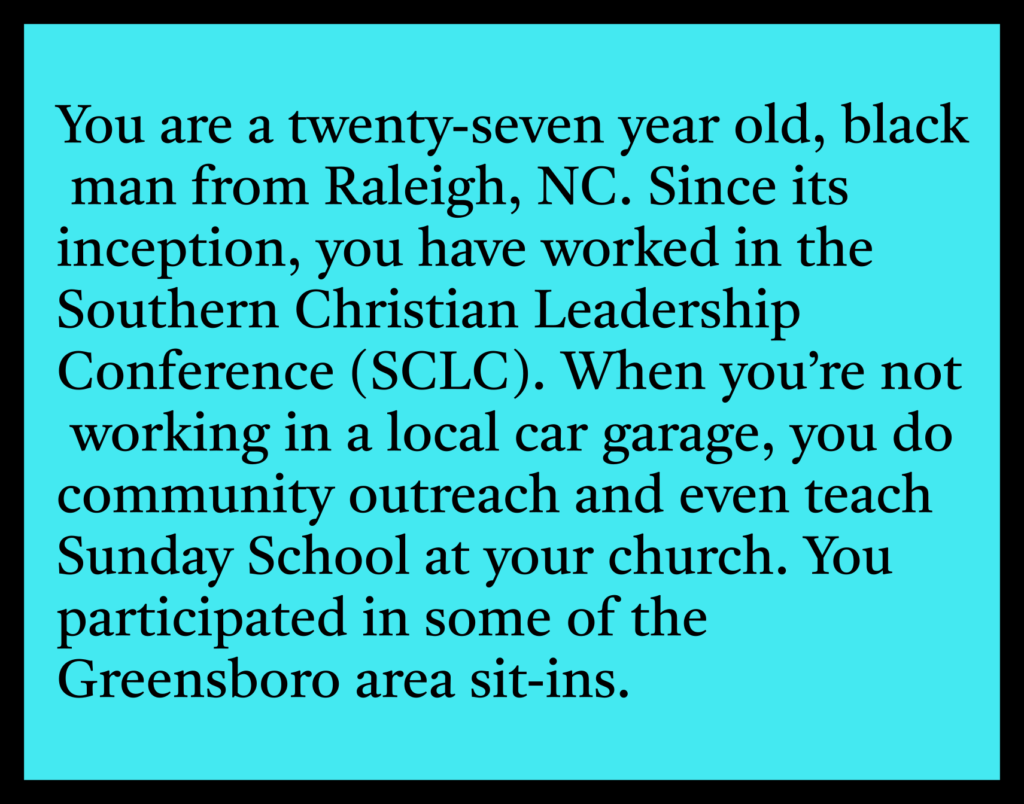

Why do you get involved! You could have stayed at home in North Carolina, doing your little part in the Civil Rights Struggle, but doing it where people know you, and where you always know where to go when there’s danger. You’re not afraid of confrontation. You were one of the students who took part in the Lunch-counter sit-ins in Greensboro. You refused to leave your seats in the white-only section after you’d been told you’d get nothing. You put up with the local boys’ insults, the punches, the ketchup and sugar poured on you, and you held your ground. You were looking beyond their anger, beyond your own anger, because you had a fiery ideal that nonviolent tension could change the hearts of people as misguided and mean as any of these kids. If things got worse, you knew you were on home ground; you were fighting, nonviolently, on familiar turf, and that made a difference. Even now, walking on the side of Georgia road, you still could feel the warm pride of the work you’d done back home.

But now you were in Georgia. You’d been here once to visit relatives, but that was long ago, and under different circumstances. You were not on friendly ground, and you could feel it. An unwritten rule in the South said that a black man should not be out at night near white neighborhoods; the local boys kept their eyes open for such opportunities. Each time a car passed, you imagined a beer bottle crashing into the back of your head, or a car unloading, figures approaching. There; the sun’s down and the twilight has settled in.

Suddenly, headlights swerve behind you. A car stops and one door opens. Maybe it’s not a crowd of white boys; maybe just the police. But then again, is that any better? You’re not from this town, you’re not from this state, and no one knows where you are to come looking for you. You keep walking, until…

“Hey, hey there son.”

You keep walking.

A College-Level Academic Game based on the variety of ways that Civil Rights groups in the 1960s organized protest activities to combat the injustice of Segregation and everything tied to it. Students give speeches and enter negotiations for victory objectives from the viewpoint of historically-based characters.

The Struggle for Civil Rights, Player's Handbook.....$29.95

(Shipping in Cart includes a fulfillment fee)

(Shipping to Canada and USA addresses)

table of contents

Introduction 5

Ch. 1 Nonviolent Tension and Resistance 29

Ch. 2 Philosophical Positions of the Factions 33

Ch. 3 Introduction to Module I: Dorchester 1963,

The Struggle for Nonviolent Tension 41

Ch. 4 Introduction to Module II: Memphis 1966,

The Struggle for Black Power 47

Appendix I:

Civil Rights History and the Long Road

Already Traveled 53

Appendix II:

Events, Institutions and Movements Shaping

Post-Brown v. Board of Education 81

Appendix III:

Introduction to Highlander Folk School 121

Appendix IV:

Primary Readings for The Struggle For Civil Rights 149

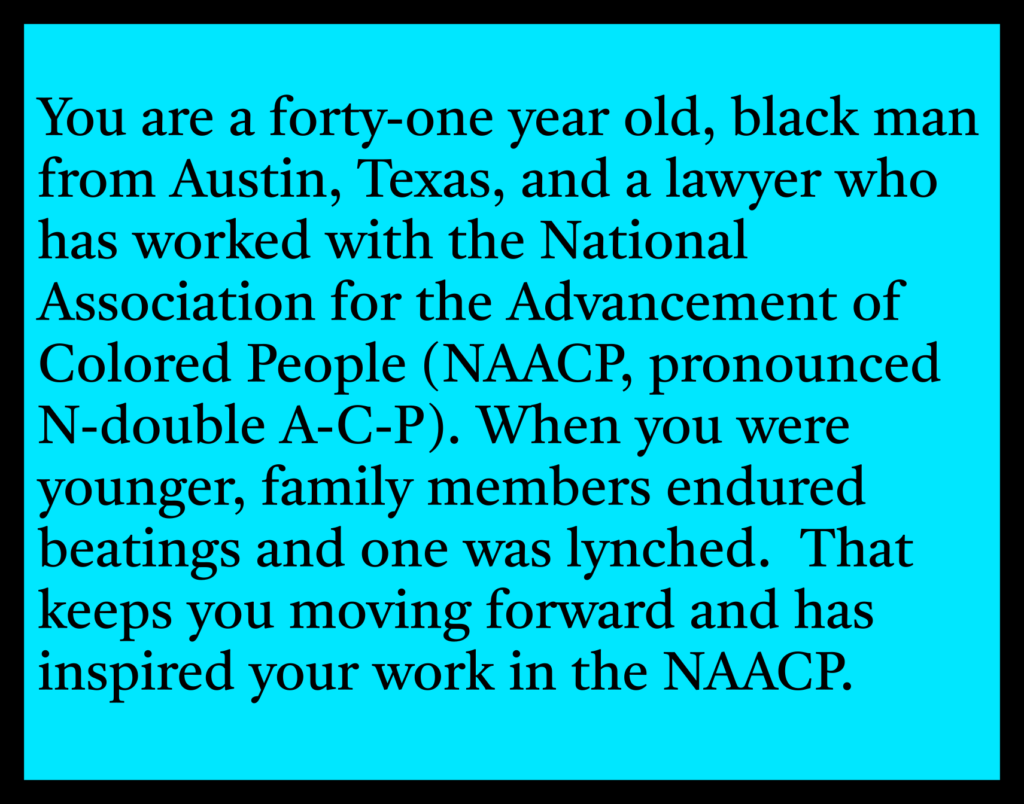

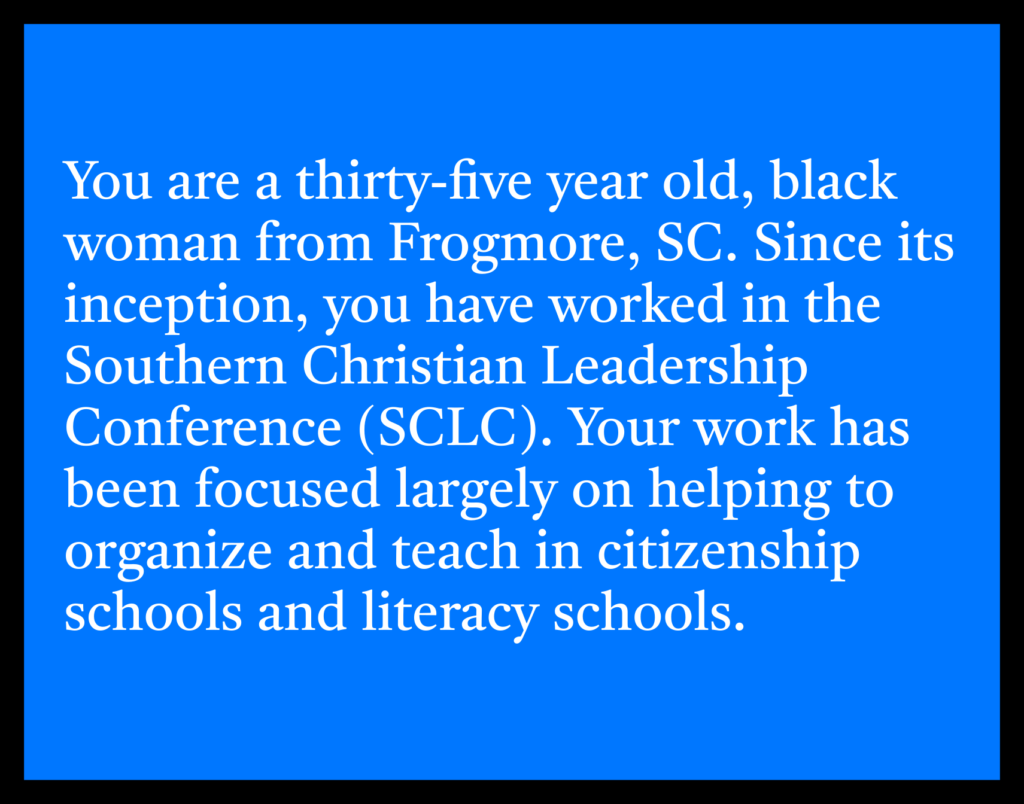

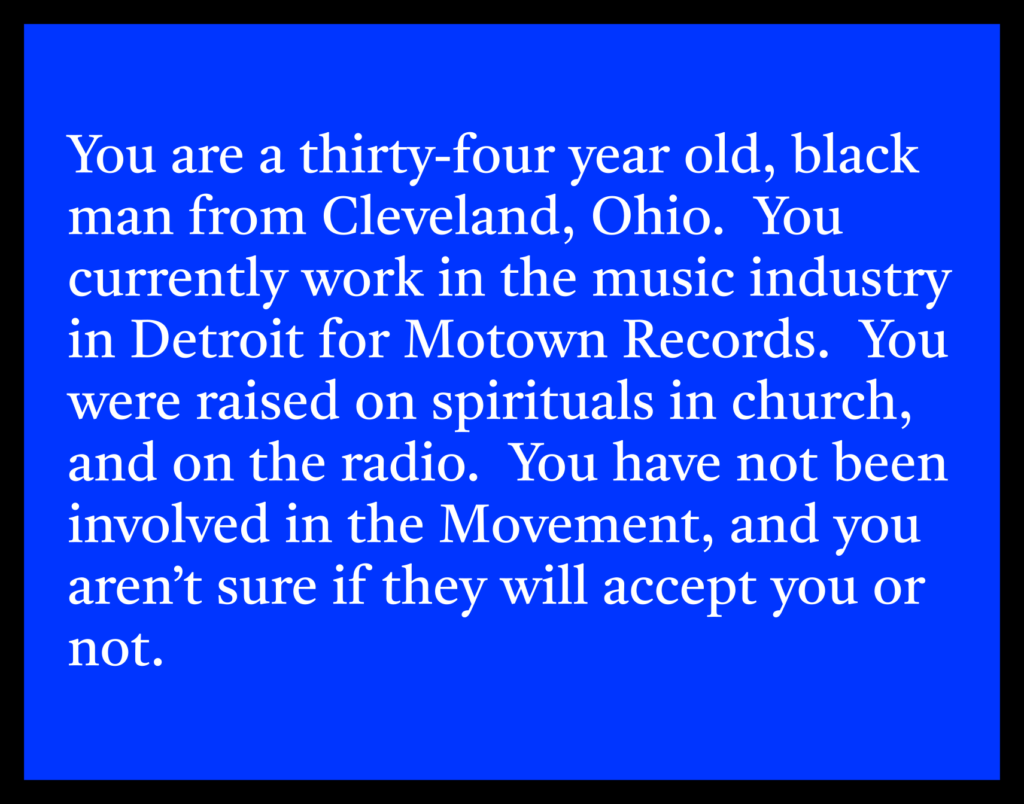

The Pedagogy of Academic Games

The Struggle for Civil Rights is a college-level, academic game designed to be used with courses dealing with courses including historical studies of the American 1960s, courses on Black Studies, Peace Studies courses, as well as First Year Seminars. Students learn course content through active learning, in the form of acting out historically based roles in a dramatic-like setting. To play their roles, students must read, discuss and debate key issues, concepts, methods, ideals, and other factors as they work (most in groups called factions) to advance specific victory objectives. Voting is the main way that final decisions are made by the students playing their roles, but students put their knowledge to work before the voting takes place as they try to persuade other characters to support or abandon various victory objectives. They also attempt to work compromises by focusing the discussion on historical, religious, philosophical and cultural topics. The Player’s Handbook has a wealth of information, as do the required readings outside the Player’s Handbook. To play the game well, students realize that they not only need to understand the beliefs and goals of their own character and faction, but that of others in the game as well, so they they can better decide with whom they may be able to strike alliances of one victory objective or another. Students often put quite a bit more energy into researching their roles because of the semi-competitive nature of the game and the camaraderie within their faction. There are also special characters who are not part of a faction (wildcards), who have their own specific victory objectives.

The Gamemaster (GM) is like a coach of a sports team. He or she helps set the game in motion, distributing role sheets, meeting with students to discuss questions about playing their role, meeting with factions as well as wildcards, and giving some introductory lectures on subjects that will be central to the upcoming discussions and debates. The GM does quite a bit of work preparing the game, and then has to work behind the scenes while the game is being played. This is unnerving for some faculty who are used to controlling their classrooms, but they need to remember that coaches have to stay on the sidelines. They can pass notes, they can send emails or text messages, but they have to restrain themselves from the game itself: that is for the students. The students will shine if given a chance; you have to trust them. No really; you have to trust that passive, lethargic students will become active, debating, debunking, diabolically clever participants in the game. If you have participated in a Reacting workshop, you have seen this firsthand. If you have watched videos of Reacting classes online, you have some idea what it’s like. But until you are the GM, you don’t know exactly what it feels like, how different it is from your ‘normal’ classroom experience, how hard it will be to hear a student say something incorrect, and how satisfying it will be when another student stands up and offers the correction. Things will go wrong at times, and behind the scenes (emails, texts, conversations before or after class) you, the GM, will coach your students on what went well and what needs improved. You will see sides of them you never dreamed existed, and you will see them excited about class. The authors have worked with Reacting to the Past over the years, doing seminars in New York and Birmingham, and getting feedback from professors using the game in their classes across the country. The 2015 version of the game has only a few changes from the 2012 version, and this is mainly in the Victory Point system.

Dorchester 1963: The Struggle for Nonviolent Tension

The success of Civil Rights campaigns in the 50s, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, inspired further activities in the 1960s. The student sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters in Greensboro, NC, in early 1960, were an example of a nonviolent protest that struck a chord, with both supporters and detractors. People who supported the students, often students themselves, saw it as a polite effort to do sometime fairly simple and fundamental: eat at a lunch counter. The students who openly broke the segregation laws were not demanding food for free; they asked politely and had money to pay, just as anyone might. It seemed absurd that such a basic need would be denied just because society was still in the habit of living out a system of segregation. Other students soon wanted to follow the example of those in the Greensboro Woolworth store.

But the sit-ins also drew the attention of local, European-Americans, some of whom decided to do their best to make the sit-in experience as unpleasant as possible, by harassing those who participated (whether the protesters were European-American or African-American). They poured ketchup and sugar on the protesters; some put out their cigarettes on the back of protester’s necks. These were the less violent ones. Those people who were more violent used bats to harm some of the protesters.

Here, however, the protesters were drawing out the contradiction of the Jim Crow South. How could people claim that segregation was the best and most proper way to order relations in society, when it allowed such ignorance, hatred and violence to fester under a facade of civility? How could segregation be regarded as necessary to guard the moral purity of European-American children, if many of them could carry out such atrocious actions as they entered adulthood?

Drawing out this contradiction was difficult and dangerous, however. The emotional and physical toll on the protests themselves was high enough. But there was also the toll of going to jail, where the temperament of the police officers, in many cases, did not differ significantly from that of the local, European-Americans who had harassed them at the lunch counter.

Initially, organizers raised funds to make bail, but by early 1961, such efforts were draining money that civil rights organizations needed. Members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) decided to reverse things and opt for “jail, not bail” in order to shift the financial strain away from civil rights organizations, and put it on the local, segregationist establishment instead. Tom Gaither, a CORE field secretary, led a group of students from Friendship Junior College in Rock Hill, SC, in a sit-in at a local McCrory’s store. The majority did not post bail and spent a month on a prison farm doing menial labor, but their actions drew support, while taxing the resources of the establishment. They sang protest songs to keep their spirits up.

Some of this approach was used in the protests in Albany, GA, the following year. Between 1961 and 1962, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized protest activities to address an array of problems and ultimately to end segregation, but there were soon difficulties between various local and national groups.

One of the initial problems was, in some ways, generational. African-American adults in Albany who had leadership positions in local the chapter of the NAACP and similar organizations did not collaborate well with the younger SNCC organizers who had come to town. Some felt that their community already had organizations in place, and were doing their best to address problems themselves. Some distrusted outsiders who were unaware of the local history. Two SNCC organizers, Charles Sherrod and Cordell Reagon, began to devote less time to working with adults in Albany, and more time trying to organize high school and college-age members of the African-American community. This seemed to further distance them from adults in the community, some of whom did not want to be seen with the SNCC organizers in public. Officials at the local Albany State College tried to discourage students from working with SNCC, eventually dismissing some and threatening to expel others. The adults in the African-American community, by and large, also seemed uncomfortable with the kinds of activities that SNCC was planning, such as testing local compliance with the new Interstate Commerce Commission’s regulations banning segregation at places of interstate travel (regulations prompted by the bloody “freedom rides” that CORE, SCLC and SNCC had carried out recently).

In the wake of what some regard as a failure and a slowing down in the momentum of the civil rights movement, King and others decided that they needed to meet face to face to discuss what would be the best way to go forward. A retreat at Dorchester, GA, was planned for 1963, so that SCLC and others could better plan how to move forward with protests in Birmingham, AL, Louisville, KY, or wherever.

Memphis 1966: The Struggle for Black Power

The March on Washington took place in August, 1963, and President Kennedy was assassinated in November. The Civil Rights Act, signed into law by President Johnson July 2nd, 1964, was viewed by some as a tribute to the slain President. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 addressed discrimination, chiefly in public accommodations and employment.

While legislation was being advanced, registration was advancing as well, but at a high cost. The Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, while registering large numbers of black people who had never before voted, opened with the brutal murder of three civil rights workers by a mob in Philadelphia, MS, in which the Sheriff, Cecil Price, was actively involved.

After this kind of sacrifice, participants in the summer voter registration drive were sharply disappointed at the 1964 Democratic Convention when their bid to seat an integrated “Freedom” delegation in place of Mississippi’s segregated one was rebuffed. It was clear to them that candidate Lyndon Johnson was behind this, seeking to keep Southern voters from bolting the Party. His running mate Hubert Humphrey brought them offers of a compromise-seating two “at large” delegates and explicit instructions that outspoken local activist Fannie Lou Hamer be not admitted. Rejecting the compromise, it became hard for many members of SNCC to trust white politicians at all after this.

The 1965 Voting Rights Act passed in the wake of the Los Angeles Riots, which left 50 square blocks of the city leveled as if it had been bombed. The 1968 Fair Housing Act passed in the wake of the riots that erupted after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Movement since then has been hard pressed to find moments uniquely suited to celebration. There are reasons for this, rooted in the historical context of the time as well as in the strategic and tactical decisions made by movement leadership. We will use as an example the response of the civil rights leadership to James Meredith’s decision to show that blacks no longer needed be afraid in Mississippi, by embarking on a “March Against Fear,” from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, a distance of over two hundred miles.

Meredith was still hated in Mississippi as the first black to integrate Ole Miss, under heavy federal guard. On the second day of his march, only a few miles into the Mississippi border, a white racist pumped four rounds of bird shot into Meredith with a shotgun, yelling “I only want James Meredith” as reporters and members of Meredith’s entourage dived for cover. Meredith was hospitalized in Memphis, in serious, but not critical condition.

Word of the shooting reached participants at a White House Conference, “To Fulfill These Rights.” The conference had been convened by President Lyndon Johnson after a 1965 speech to the graduating class of Howard University, in which he promised to move the cause of civil rights forward in a massive way. Several of the leaders present at the conference, including Roy Wilkins of the NAACP and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. of SCLC, flew to Memphis to consult with Meredith, and there decided to continue his March. Floyd McKissick, the new Chair of CORE, had already pledged to do so, and a call went out to Stokeley Carmichael, newly elected Chairmen of SNCC, for his organization to participate as well.

All the leaders met at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis to discuss strategy.

Each participant has role instructions regarding the personal background, preferred issues, and organizational imperatives that affected each leader. The participants are not required to make the same choices as the historical character, but they must be true to the character.

Opening Narrative: Memphis 1966

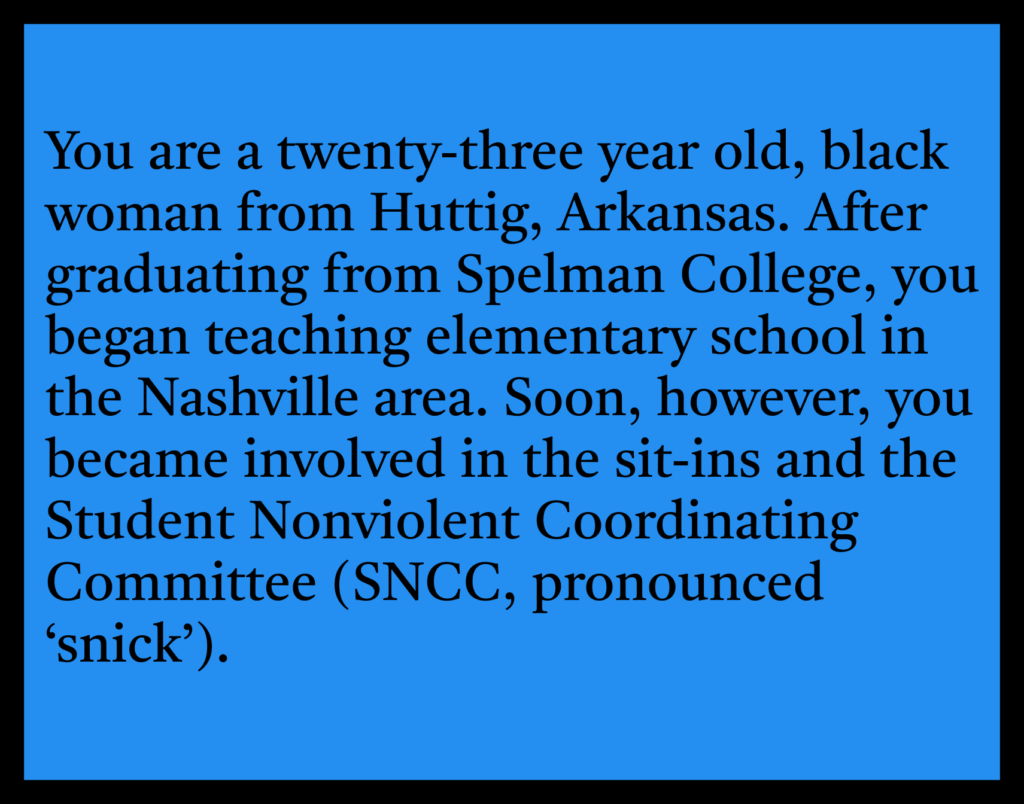

You knew that Ella had worked with SNCC further South after the Nashville sit-ins that you’d both participated in, but she fills in a few details you didn’t know about, while you let her know what had been going on in Nashville since she left. You and Ella had never been the closest of friends in Nashville, but you were friendly. Both of you had been at Dorchester, roughly three years ago, and after a few miles roll by, Ella starts to chuckle.

“I was sitting here, and I just, kind of, felt this heat on the side of my face–”

“—What?”

“—And I looked over and saw this woman staring at me—

“Now, you know I didn’t mean to stare at–”

“and I thought, ‘this woman’s gonna try to steal my earrings!’”

“Oh heavens!”

“—the way you were staring.” She smiles, and then you laugh as you glance back

at the window.

“They are nice earrings?” you say.

“Well, I know these bus trips can put me right to sleep sometimes.” she suggests.

“Yes, well….It’s funny Ella.” You shift around in your seat, and Ella quietly waits for you to continue. “I was just looking at that broken window up there.”

“What? Oh yeah, look at that.”

“It just…well, brought up memories of that ride I took.”

Ella tilts her head from left to right and leans closer. “Diane, you mean one of the freedom rides?”

“This is…this is my first bus ride of any length since then.”

“Oh no?”

“I saw that broken win–” your voice breaks a little, and you feel Ella’s warm hand on your shoulder, as a wave of feelings rushes across your face. But it’s only for a moment; you’re okay.

Ella tries to get you talking: “Now, I’ve forgotten when you took that ride.”

You close your eyes for a second as you answer her: “I was at Anniston.”

“Oh no.”

“Not the first bus, thank goodness, though we didn’t fare a great deal better. You know, I was just staring at that window and thinking how such a little thing can bring back so many memories.”

Now Ella was squinting at you again. “So, you took a car to Dorchester…”

“Um-hum.”

“…and now, you’re on this bus.”

“Yes.”

“Diane, I’m almost sure we’re going the same way today.”

“Isn’t that how a bus works?”

“No, no; I mean you’re going to Memphis for the meeting about Meredith’s March.”

You look at her and shake you’re head. “You too?” You both chuckle.

“Yes, well,” she explains with some bravado, “you know, someone’s got to set up the coffee pots!”

“Oh really!”

“Yes, yes, and the sugar–, oh my, someone’s got to get the sugar on the table for everyone.”

“Ella, you–” as you make your comment, a white man with grayish-white hair, reddish cheeks and glasses turns around in his seat, a few rows up, and stares at you until you both look down. After a little while he shakes his head and turns back around abruptly. You both feel the need to keep the conversation going, but more discreetly, in lower voices.

“There are still lots of folks,” Ella whispers, “who just can’t stomach coffee integrated with sugar!”

“Um-hum.” you chuckle quietly as you squeeze your lips together thinking about that man a few rows up.

“Those men keeping you busy in SNCC, Ella?”

“You know, some things never change. Rights for the black man now–”

“Oh yes.”

“—yesterday,”

“I hear ya.”

“But the black woman…is still better at making coffee, so…”